Clustering Multivariate Longitudinal Data using Tensor Product Smoothing Splines

demo.Rmd1. Introduction

Electronic health records (EHR) provide a wealth of patient information with repeated measures of multiple lab values over time. Such longitudinal datasets have become increasingly common as medical records are computerized, offering opportunities in clinical research to examine biomarkers as they change over time rather than at one single timepoint. A common approach to analyzing trajectories of lab values is to identify subgroups of patients with similar characteristics, and to further assess association between group membership and distal outcomes (Aghabozorgi, Shirkhorshidi, and Wah 2015; Nylund-Gibson, Grimm, and Masyn 2019). Two general methods are often employed to classify trajectories: latent trajectory methods such as growth mixture modeling (GMM) and group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) (Nest et al. 2020), and unsupervised machine learning methods such as k-means clustering. While there have been extensive applications where longitudinal data is grouped based on the trajectory of a single biomarker, there are fewer studies that focus on grouping multivariate trajectories of correlated variables.

Latent trajectory methods assume an underlying latent grouping

variable such as “severity of disease” that is manifest in the observed

variables. The posterior probability of class membership is estimated

for each individual using maximum likelihood methods. GMM estimates a

mean growth curve for each class and represents individual variation

using random effects (Muthen and Muthen

2000). The package lcmm (Proust-Lima et al. 2022) in R ( Core Team 2017) can be used to estimate growth

mixture models with various extensions, including the

multlcmm() function for multivariate trajectories. GBTM, on

the other hand, does not use random effects to capture individual

differences and assumes equal variance across all times and classes

(Herle et al. 2020). GBTM is also

implemented in the lcmm package, as well as in PROC TRAJ

Jones and Nagin (2007)] in SAS ( Institute Inc. 2016). A multivariate extension

has also been developed for PROC TRAJ. These methods provide valuable

tools, but they require distributional assumptions and can have high

computational costs (particularly GMMs) and potential convergence

issues, especially when applied to large datasets or datasets with

outliers (Den Teuling, Pauws, and Heuvel

2020).

Clustering methods have also been used extensively to classify

trajectory data. These algorithms, such as k-means, k-medoids, and

hierarchical clustering, have a lower computational cost compared to

methods such as GMM, but they require that data be measured at the same

timepoints for each individual if the clustering is done on raw data.

This feature is rarely found in clinical datasets, so a pre-processing

step is sometimes implemented, where trajectories are estimated using

splines, and the clustering algorithms are applied to spline basis

coefficients or fitted spline values Abraham et

al. (2003); D’Urso et al. (2021)].

Smoothing splines offer the additional advantage of noise and data

reduction. A number of multivariate clustering methods have been

proposed, including clustering on p-values from hypothesis tests for the

difference between autoregressive parameter estimates (Maharaj 1999), using principal components

analysis to calculate a degree of similarity , and wavelet analysis

(D’Urso and Maharaj 2012). A number of R

packages have been developed to cluster trajectory data. The package

traj (Sylvestre et al. 2006;

Leffondree et al. 2004) implements a stepwise method where 24

change indices are computed to assess different aspects of the

longitudinal pattern, then a principal components analysis is used to

determine the most important features, and lastly k-means clustering is

conducted on the change indices. The kml R package (Genolini et al. 2015) utilizes k-means

clustering on trajectory data with imputation methods available for

missing data. It has been extended with the kml3d package

(Genolini et al. 2015), which clusters

based on two trajectories. A recent paper comparing traj,

kml, and lcmm found that kml

showed the best clustering accuracy, cluster separation, and stability

(Verboon and Pat El 2022). This indicates

that non-model-based methods such as k-means have the potential to work

as well or better than more complex and computationally costly methods

such as GMM.

The TPSClus package utilizes non-model-based methods to

efficiently identify clusters in datasets with three or more trajectory

variables of interest, with the efficiency to handle large datasets such

as those sometimes found containing EHR data. Rather than imputing

missing data, the method fits smoothing splines to the trajectories of

each individual. In order to account for the likely correlation between

these variables, multidimensional tensor product splines are used,

implemented using a generalized additive model (GAM) in R package

mgcv (S. N. Wood 2011, 2003).

The user then has the option of conducting fuzzy c-medoids clustering on

either the spline basis coefficients or the fitted values at

user-defined points. In addition, there is an option for the inclusion

of a noise cluster for outliers. The fuzzy clustering is implemented

using R package fclust [Ferraro,

Giordani, and Serafini (2019)}, and it yields a degree of cluster

membership for each individual. The clusters can then be used as

predictors in a generalized linear model (GLM) for a distal outcome if

desired. The package offers numerous plot functions, and the ability to

predict cluster membership and distal outcomes for new datasets.

In section 2, we examine the data structure and provide a review of

tensor product splines. In section 3, we review fuzzy clustering methods

and detail methodology for the inclusion of fuzzy clusters as predictors

in GLMs. In section 4, we provide an overview of the package

TPSClus, demonstrating the primary functions and features.

Section 5 concludes and summarizes.

2. Smoothing multivariate longitudinal data

In most clinical databases where measurements are taken over time, it is rare that all individuals are measured at the same timepoints or with the same frequency. As a result, a pre-processing step must be implemented prior to applying a partitional clustering algorithm such as k-mean, k-medoids, or hierarchical clustering. One common approach is the use of smoothing splines (Abraham et al. 2003; D’Urso et al. 2021; Iorio et al. 2016), which have the added benefit of reducing measurement error and noise . In the case where there are multiple trajectories of interest, we can incorporate the correlation between those trajectories into the smoothing process by using multidimensional tensor product smoothing splines.

2.1 Data structure

A multivariate time series can be structured as a three-dimensional array in the form of subjects \(\times\) variables \(\times\) times (D’Urso, De Giovanni, and Massari 2018; D’Urso 2000). The trajectories for a single individual \(\mathbf{Y}_{i}=\{y_{izt}:z=1 \dots Z; t=1 \dots T_{i}\}\), where \(Z\) is the number of variables and \(T_i\) is the number of observations for subject \(i\), can be plotted as a plane in Cartesian three-space, as seen in Figure 1.

The instantaneous, or cross-sectional dissimilarity between two trajectories measured at the same timepoints \(\mathbf{Y}_i\) and \(\mathbf{Y}_{i'}\) can be defined using the squared Euclidean distance: \[{}_{1}d_{ii'}^{2}= \sum_{t = 1}^{T} \| \mathbf{y}_{it} - \mathbf{y}_{i't} \|^2.\] This distance does not, however, take into account the longitudinal nature of the data. One simple approach that allows us to capture information about the intervals between timepoints is to define \(\mathbf{v}_{it} = \mathbf{y}_{it} - \mathbf{y}_{i(t-1)}\) as the variation, or slope, of trajectory \(\mathbf{Y}_i\) in the interval \([t-1,t]\). Then a longitudinal dissimilarity measure between \(\mathbf{Y}_i\) and \(\mathbf{Y}_{i'}\) can be defined as: \[{}_{2}d_{ii'}^{2}= \sum_{t = 1}^{T} \| \mathbf{y}_{it} - \mathbf{y}_{i't} \|^2 + \sum_{t = 2}^{T} \| \mathbf{v}_{it} - \mathbf{v}_{i't} \|^2.\] A mixed approach can then be used to simultaneously consider both the cross-sectional and longitudinal features, where the dissimilarity is given by: \[d_{ii'}^{2}= \sum_{t = 1}^{T} \| \mathbf{y}_{it} - \mathbf{y}_{i't} \|^2 + \sum_{t = 2}^{T} \| \mathbf{v}_{it} - \mathbf{v}_{i't} \|^2.\]

2.2 Tensor product splines

In order to smooth multiple trajectories simultaneously, tensor

product splines can be fit using a GAM. The basic approach, described in

detail by (S. N. Wood 2017; Simon N. Wood

2006), is to begin with marginal smooths of the covariates of

interest, in this case the variable and the time. A tensor product is

then used to create a smooth of multiple variables from these marginal

smooths. Here we have two covariates, \(z\) (variable) and \(t\) (time). A low-rank base can be chosen

for each, representing the smooth function of each covariate, \(f_z\) and \(f_t\): \[f_{z}(z)= \sum_{j=1}^{J} \alpha_j a_j(z)

\quad\mathrm{and}\quad

f_{t}(t)= \sum_{k=1}^{K} \beta_k b_k(t)\] where \(\alpha_j\) and \(\beta_k\) are parameters, \(a_{j}(z)\) and \(b_{k}(t)\) are the basis functions, and

\(J\) and \(K\) are the corresponding number of basis

functions. If we then allow the parameters of \(f_z\) to vary smoothly with \(t\), \(f_z\) can be converted into a function of

\(z\) and \(t\). We use the basis for \(t\) to get: \[\alpha_{j}(t)= \sum_{k=1}^{K} \beta_{jk}

b_{k}(t)\] and it then follows that \[f_{zt}(z,t)= \sum_{j=1}^{J} \alpha_j a_{j}(z) =

\sum_{j=1}^{J} \sum_{k=1}^{K} \beta_{jk} b_{k}(t)a_{j}(z).\] The

set of observations of \(z\) and \(t\) has model matrices for the marginal

smooths, \(\mathbf{X}_z\) and \(\mathbf{X}_t\). The model matrix \(\mathbf{X}\), which maps parameters \(\beta_{jk}\) (arranged into a vector \(\mathbf{\beta}\)) to the evaluated function

\(f_{zt}(z,t)\) at \(z\) and \(t\), can be calculated using a Kronecker

product of these model matrices for the marginal smooths. The \(i\)-th row of \(\mathbf{X}\) is given by: \[\mathbf{X}_{i}= \mathbf{X}_{zi} \otimes

\mathbf{X}_{ti}\] In order to smooth this tensor product basis,

the roughness is also measured using marginal smooth functions, with the

assumption that each has an associated function that measures the

roughness of the function and can be expressed as a quadratic form in

the marginal parameters. Here, cubic spline penalties are used as the

marginal penalties, so the roughness of \(f_{zt}\) can be measured as: \[\begin{equation}

J(f_{zt})= \int_{z,t} \left[ \lambda_{z} \left(

\frac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial z^2} \right) ^2 + \lambda_t \left(

\frac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial t^2} \right) ^2 \right] \mathrm{d}z

\mathrm{d}t

\end{equation}\] where \(\lambda_{z}\) and \(\lambda_{t}\) are smoothing parameters that

control the tradeoff in roughness in different directions and allow the

penalty to be independent of the scaling of the variables. The

coefficients and smoothing parameters of this tensor product smooth are

estimated in a GAM using R package mgcv.

3. Fuzzy clustering of time series

After the multiple time series have been smoothed, a clustering algorithm can be applied. One option is to cluster on the spline coefficients as in D’Urso et al. (2021) and D’Urso, De Giovanni, and Vitale (2022). Alternatively, clustering can be conducted on fitted values at the spline knots or other chosen timepoints, as well as the slopes between points, with the distance defined as in section 2.1. If the primary interest is in the shape of the trajectory, the shape can be isolated by centering on the individual means of each trajectory as in (Heggeseth and Jewell 2018). These clusters allow the identification of individuals with similar characteristics, and cluster membership might subsequently be used as a prognostic variable in a GLM for a distal outcome.

3.1 Fuzzy clustering algorithm

The k-means algorithm partitions objects into \(k\) clusters so that each object is placed into the cluster with the nearest mean, usually measured by the squared Euclidean distance. The number of clusters \(k\) is pre-specified, and the algorithm is iterative, with means recalculated for each cluster at each step, until within-cluster variance is minimized (Hastie, Tibshirani, and Friedman 2009). The k-medoids clustering algorithm, also called the partitioning around medoids (PAM) approach, is similar to the k-means algorithm, except that it uses observed values within the data as the centers, or medoids, of each cluster. This method has been shown to be more robust to outliers than the k-means algorithm (Arora, Deepali, and Varshney 2016; Kaufman and Rousseeuw 2009).

K-means and k-medoids algorithms provide “crisp” partitions where individuals are assigned to exactly one cluster. Fuzzy c-means (Bezdek 2013) and fuzzy c-medoids (Krishnapuram et al. 2001) clustering methods have been developed as “fuzzy” counterparts, where an individual’s membership degree is calculated for each cluster. Fuzzy clustering offers an advantage in real applications when there are not clear boundaries between clusters (Alonso et al. 2021), and it provides additional information regarding the certainty of the cluster assignments (Everitt 2011), while still being computationally efficient.

If \(\mathbf{X}={\mathbf{x}_i |i=1, \dots ,n}\) is a set of values for \(n\) subjects, we can let \(\mathbf{Q}={\mathbf{q}_1, \mathbf{q}_2, \dots , \mathbf{q}_c}\) be the set of cluster means or cluster medoids, where the \(\mathbf{x}_i\) and \(\mathbf{q}_j\) are scalar for univariate data and mathbfors for multivariate data and \(c\) is the number of clusters. In fuzzy c-medoids clustering, \(\mathbf{Q}\) will be a subset of size \(c\) of \(\mathbf{X}\). Then the fuzzy c-means or fuzzy c-medoids algorithm will minimize \[\begin{equation} \mathop{\arg \min}\limits_{\mathbf{Q}}= \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{c} u_{ij}^{m} \|\mathbf{x}_{i} - \mathbf{q}_j \|^{2}. \end{equation}\]

In this objective function, \(u_{ij}\) represents the degree of membership of \(\mathbf{x}_i\) in cluster \(j\), and is most often defined by:

\[\begin{equation}

u_{ij}= \frac{1}{\sum_{k=1}^{c} \left( \frac{\|\mathbf{x}_{i} -

\mathbf{}_j \|}{\|\mathbf{x}_{i} - \mathbf{q}_k \|}

\right)^{\frac{2}{m-1}}}

\end{equation}\] where \(m\) is

the “fuzziness” parameter, \(m \in

[1,\infty)\). Higher values of \(m\) indicate a higher fuzziness, where

individuals are more likely to belong to more clusters. There is not a

widely accepted optimal value for \(m\), but it is related to the number and

separation of clusters in the dataset (Huang et

al. 2012). As \(m \to 1_{+}\),

the fuzzy clustering algorithm reduces to a hard clustering algorithm,

and as \(m\) increases, clusters blend

together. In 2019, Zhou and Yang (2019)

published an experimental study where they found that the optimal value

for most datasets is \(m = 1.2\), and

this is the default value used in the TPSClus clustering

functions.

A number of strategies have been introduced to reduce the influence of outliers in the clustering process. One method is the introduction of an artificial \((c+1)\)-th cluster, called a noise cluster, for the outlying values. Individuals with a distance greater than \(\delta\) from the medoids are classified into the noise cluster. The distance \(\delta\) is generally chosen so that it is the average distance between individuals and cluster means, but it may be pre-specified to control the number of individuals classified as outliers. If a noise cluster is included, the equation for \(u_{ij}\) is replaced by: \[\begin{equation} u_{ij}= \frac{\left[ \frac{1}{|\mathbf{x}_{i} - \mathbf{q}_k \|^2} \right] ^{\frac{1}{m-1}}}{\sum_{k=1}^{c} \left[ \frac{1}{\|\mathbf{x}_{i} - \mathbf{q}_k \|} \right]^{\frac{1}{m-1}} + \left[ \frac{1}{\delta^2} \right]^{\frac{1}{m-1}}} \end{equation}\]

and the degree of membership in the noise cluster is \[\begin{equation} u_{i(j+1)}= \frac{\left[ \frac{1}{\delta^2} \right] ^{\frac{1}{m-1}}}{\sum_{k=1}^{c} \left[ \frac{1}{\|\mathbf{x}_{i} - \mathbf{q}_k \|} \right]^{\frac{1}{m-1}} + \left[ \frac{1}{\delta^2} \right]^{\frac{1}{m-1}}} \end{equation}\]

The clustering algorithm is implemented using R package

fclust (Ferraro, Giordani, and

Serafini 2019).

3.2 Including clusters as predictors in a statistical model

After identifying clusters of individuals with similar characteristics, there is often an interest in examining the association between cluster assignment and an outcome of interest. A straightforward approach is to construct a GLM using the modal cluster assignment as a categorical variable. Such an approach, however, assumes that cluster assignment is certain, which is most often not the case. Fuzzy clustering, however, provides additional information in the degree of cluster membership. This information can be incorporated into a GLM to account for the clustering uncertainty using the partial assignment method, where c - 1 dummy variables for cluster membership are used, but the degree of cluster membership is inserted into the model for each of these variables rather than a zero or one (Lythgoe, Garcia-Fiñana, and Cox 2019). Using a GLM also allows additional covariates to be included in the model.

4. The TPSClus package

The TPSClus package was designed to implement the

three-step methodology described in sections 2 and 3. The

TPSfit() function fits tensor product splines to

multivariate longitudinal data. The cluster.fitted() and

cluster.coefs() functions apply fuzzy c-medoids clustering

to the smoothed data. The FKM.glm() function fits a GLM

where cluster assignment is an independent variable, incorporated using

the partial assignment method. The package requires R packages

mgcv, fclust, dplyr,

tidyr, as well as ggplot2 if graphics are

produced.

4.1 Fitting tensor product splines in TPSClus

For a simple illustration of the functionality of the

TPSClus package, we use a simulated time series dataset

containing three variables collected over a period of one year. The

dataset is structured in long format, with a subject ID variable, a time

variable, three variables measured at each timepoint, two fixed

covariates, and a binary outcome variable.

library("TPSClus")

data("TS.sim")

head(TS.sim)

#> SubjectID Time Var1 Var2 Var3 x1 x2 outcome

#> 1 17 0 4.5 10.0 5.7 0 27.9 1

#> 2 17 7 5.6 10.6 5.9 0 27.9 1

#> 3 17 35 7.0 10.1 3.9 0 27.9 1

#> 4 17 73 7.3 9.9 4.4 0 27.9 1

#> 5 17 79 7.1 12.8 5.9 0 27.9 1

#> 6 17 80 5.5 11.0 6.1 0 27.9 1The TPSfit() function fits tensor product splines on

three or more variables with repeated measures, in this case

Var1, Var2, and Var3. The splines

are fitted using the gam() function in package

mgcv with a cubic spline basis. For the time variable, the

user may choose to either specify the location of the knots, or specify

the number of knots, which will then be spaced evenly across the total

time period. It is necessary that all individuals be measured over

roughly the same time period, and that each individual has a number of

observations greater than or equal to the chosen number of knots. As

TPSfit() runs , it will produce a warning message for any

individuals who were unable to be fit by a spline with the given number

of knots, and a list of these subjects is included in the output. For a

simple fit using 5 knots for the time variable, we can run

fitsplines1 <- TPSfit(TS.sim, vars=c("Var1", "Var2", "Var3"), time="Time", ID="SubjectID", kt=5)

print(fitsplines1)

#> Object of type 'TPSfit'

#>

#> Tensor-product splines fit for 150 out of 150 subjects

#> Variables of interest: Var1 Var2 Var3

#> Time knots: 0 91 182 273 364

#> Output: GAMscoef contains model coefficients

#> Output: GAMsfitted has fitted values at times: 0 91 182 273 364

#>

#> Available components:

#> [1] "GAMsfitted" "GAMscoef" "fit_times" "vars"

#> [5] "data_long" "knots" "indiv_means" "GAMs"

#> [9] "nsubjects" "ID" "IDmatch" "error_subjects"

#> [13] "call"Splines were fit for all of the 150 subjects. The

GAMsfitted dataset contains fitted spline values at the

knots, and the GAMScoef dataset contains the spline

coefficients. By default, the function standardizes each of the

variables in order to equalize the multivariate data so that all

variables are on the same scale RN283. For each individual,

the mean of each trajectory is also produced, along with values centered

on the individual mean. These can be seen in the GAMsfitted

dataset:

head(fitsplines1$GAMsfitted)

#> Id2 SubjectID FitTime Variable x t mean_x centered_x

#> 1 1 17 0 1 -0.7351913 1 -0.11890952 -0.61628180

#> 2 1 17 0 2 -0.4458700 1 -0.05598468 -0.38988534

#> 3 1 17 0 3 -0.2976551 1 -0.17464892 -0.12300614

#> 4 1 17 91 1 -0.3394761 2 -0.11890952 -0.22056654

#> 5 1 17 91 2 -0.1960867 2 -0.05598468 -0.14010198

#> 6 1 17 91 3 -0.2530180 2 -0.17464892 -0.07836904As a default, the fitted values are calculated at the knots, but

alternate fitted values can be specified with the fit_times

option. Additional fitted values might yield better clustering results,

but will also slow down the clustering algorithm.

fitsplines2 <- TPSfit(TS.sim, vars=c("Var1", "Var2", "Var3"),

time="Time", ID="SubjectID", knots_time=c(0, 91, 182, 273, 365),

fit_times=c(46, 91, 137, 182, 228, 273, 319))

print(fitsplines2)

#> Object of type 'TPSfit'

#>

#> Tensor-product splines fit for 150 out of 150 subjects

#> Variables of interest: Var1 Var2 Var3

#> Time knots: 0 91 182 273 365

#> Output: GAMscoef contains model coefficients

#> Output: GAMsfitted has fitted values at times: 46 91 137 182 228 273 319

#>

#> Available components:

#> [1] "GAMsfitted" "GAMscoef" "fit_times" "vars"

#> [5] "data_long" "knots" "indiv_means" "GAMs"

#> [9] "nsubjects" "ID" "IDmatch" "error_subjects"

#> [13] "call"The TPSfit() function produces an object of class

'TPSfit' that can then be input into the

cluster.fitted() or cluster.coef() function to

conduct fuzzy clustering on the fitted tensor product splines.

4.2 Fuzzy clustering in TPSClus

After fitting the splines, we implement the fuzzy clustering

algorithm. A noise cluster is optional and is frequently needed for

robustness to outliers. We can examine our data for outliers using the

plot function for the 'TPSfit' object

outputted in the first step, and in this case we look at the

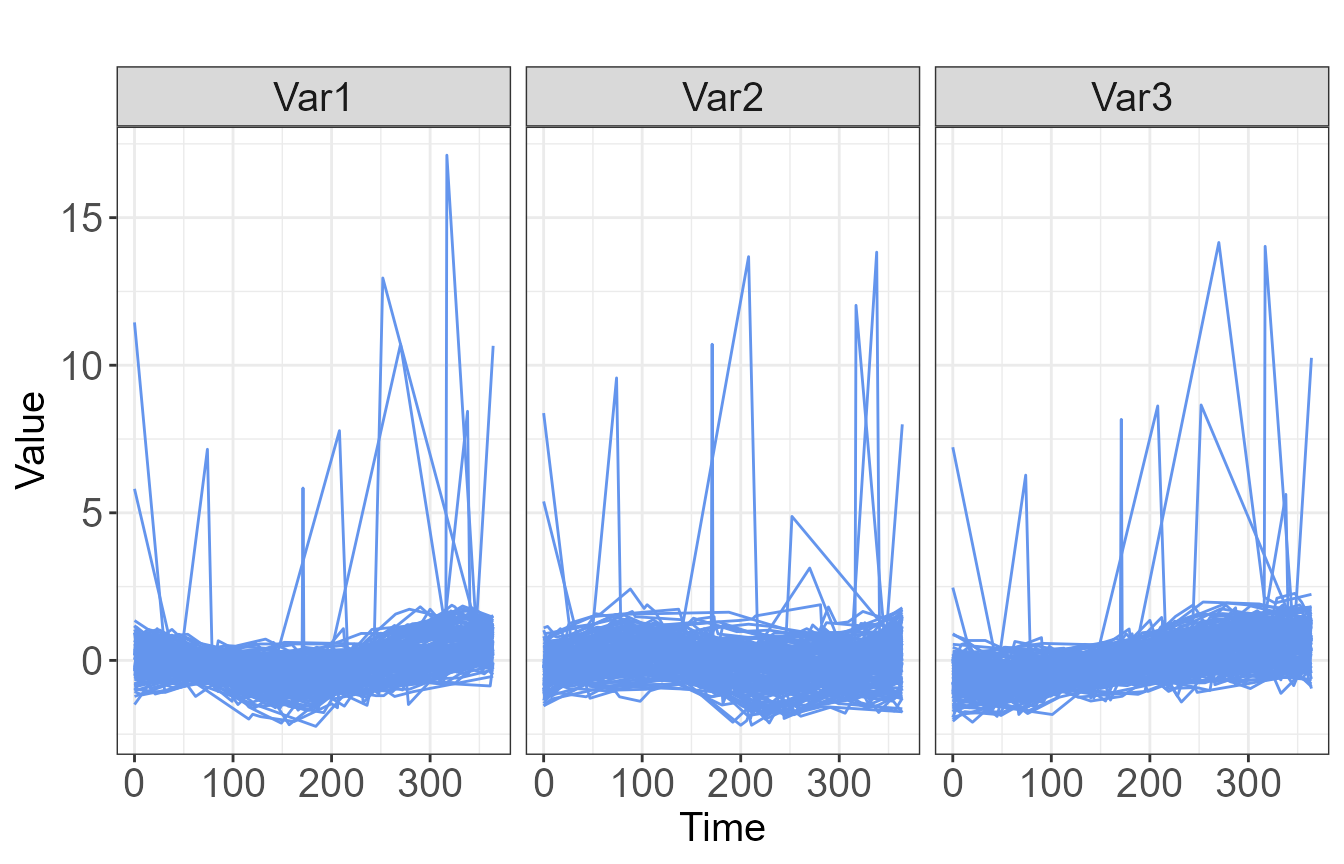

standardized raw data as shown in Figure 2.

plot(fitsplines2, type="raw")

Due to the observation of several outlying trajectories, we will

leave the default noise = TRUE option. We start by

clustering on the spline coefficients with k = 2 clusters

and 10 random starts.

ccoefs_2 <- cluster.coefs(fitsplines2, k=2, RS=10, seed=1234)

ccoefs_2$FKM_indices

#> PC PE MPC SIL SIL.F XB

#> 0.6795184 0.2448186 0.3590367 0.2246924 0.2483164 0.8582490The cluster validity indices allow for a comparison between multiple

clusterings and are helpful in the determination of the correct number

of clusters. Two commonly applied indices for fuzzy clustering are the

Fuzzy Silhouette index, here labeled as SIL.F (Campello and Hruschka 2006) and the Xie-Beni

index, labeled XB (Xie and Beni

1991). The maximum value of the Fuzzy Silhouette and the minimum

value of the Xie-Beni index are used to identify the optimal number of

clusters. The comp.FKM.indices() function in

TPSClus generates a simple table to compare validity

indices.

ccoefs_3 <- cluster.coefs(fitsplines2, k=3, RS=10, seed=1234)

ccoefs_4 <- cluster.coefs(fitsplines2, k=4, RS=10, seed=1234)

ccoefs_5 <- cluster.coefs(fitsplines2, k=5, RS=10, seed=1234)

comp.FKM.indices(list(ccoefs_2, ccoefs_3, ccoefs_4, ccoefs_5), index=c("SIL.F", "XB"), clusternames=c("k=2", "k=3", "k=4", "k=5"))

#> SIL.F XB

#> k=2 0.2483164 0.8582490

#> k=3 0.3359611 0.4794297

#> k=4 0.3210678 0.8333409

#> k=5 0.2684423 1.1316547According to the Fuzzy Silhouette and Xie-Beni indices, the optimal number of clusters for this dataset is three.

An alternate method for clustering is to cluster based on the fitted spline values and the slopes between those values. We can apply this using three clusters for comparison.

cfit_3 <- cluster.fitted(fitsplines2, k=3, RS=10, seed=1234)

comp.FKM.indices(list(ccoefs_3, cfit_3), index=c("SIL.F", "XB"), clusternames = c("coefficients", "fitted values"))

#> SIL.F XB

#> coefficients 0.3359611 0.4794297

#> fitted values 0.4814252 0.4135123Clustering on the fitted values appears to improve the clustering

results. Note that we used the default values for the

cluster.fitted() function of addslopes = TRUE

(includes the slope between points in addition to the cross-sectional

values at each point), center = TRUE (centers each

trajectory on the individual mean), and m = 1.2. The full

details of the clustering results can be viewed using the

summary function.

summary(cfit_3)

#> cluster.fitted(TPSdata = fitsplines2, k = 3, seed = 1234, RS = 10)

#>

#> 150 subjects clustered into 3 clusters + noise cluster using m = 1.2

#> Clusters based on fitted values at times 46 91 137 182 228 273 319

#> and slopes between points

#>

#> Cluster summary:

#> Cl.size Min.degree Max.degree Mean.degree

#> Clus1 49 0.303 1.000 0.965

#> Clus2 50 0.788 1.000 0.993

#> Clus3 46 0.977 1.000 0.999

#> Noise 5 0.439 0.995 0.830

#>

#> Component 'FKM_TPS' contains the fuzzy clustering details from package 'fclust'.

#> Components of 'FKM_TPS':

#> [1] "U" "H" "F" "clus" "medoid" "value"

#> [7] "criterion" "iter" "k" "m" "ent" "b"

#> [13] "vp" "delta" "stand" "Xca" "X" "D"

#> [19] "call"

#>

#> Cluster validity indices:

#> PC PE MPC SIL SIL.F XB

#> 0.94952330 0.04157604 0.92428495 0.46242525 0.48142523 0.41351228

#>

#> Output dataset 'FKM_TPS_U' contains degree of cluster membership and modal

#> cluster assignment for each object.

#> Head of dataset 'FKM_TPS_U':

#> Id2 SubjectID Clus1 Clus2 Clus3 Noise ClusModal

#> 1 1 17 4.739759e-08 1.000000e+00 2.668276e-11 4.322098e-13 2

#> 2 2 19 3.017424e-05 9.380437e-06 9.999604e-01 5.364980e-08 3

#> 3 3 34 1.025170e-08 1.000000e+00 1.407161e-12 1.454392e-14 2

#> 4 4 52 4.097481e-08 1.000000e+00 9.080800e-12 1.292300e-13 2

#> 5 5 55 1.633734e-05 5.442627e-06 9.999782e-01 2.370104e-08 3

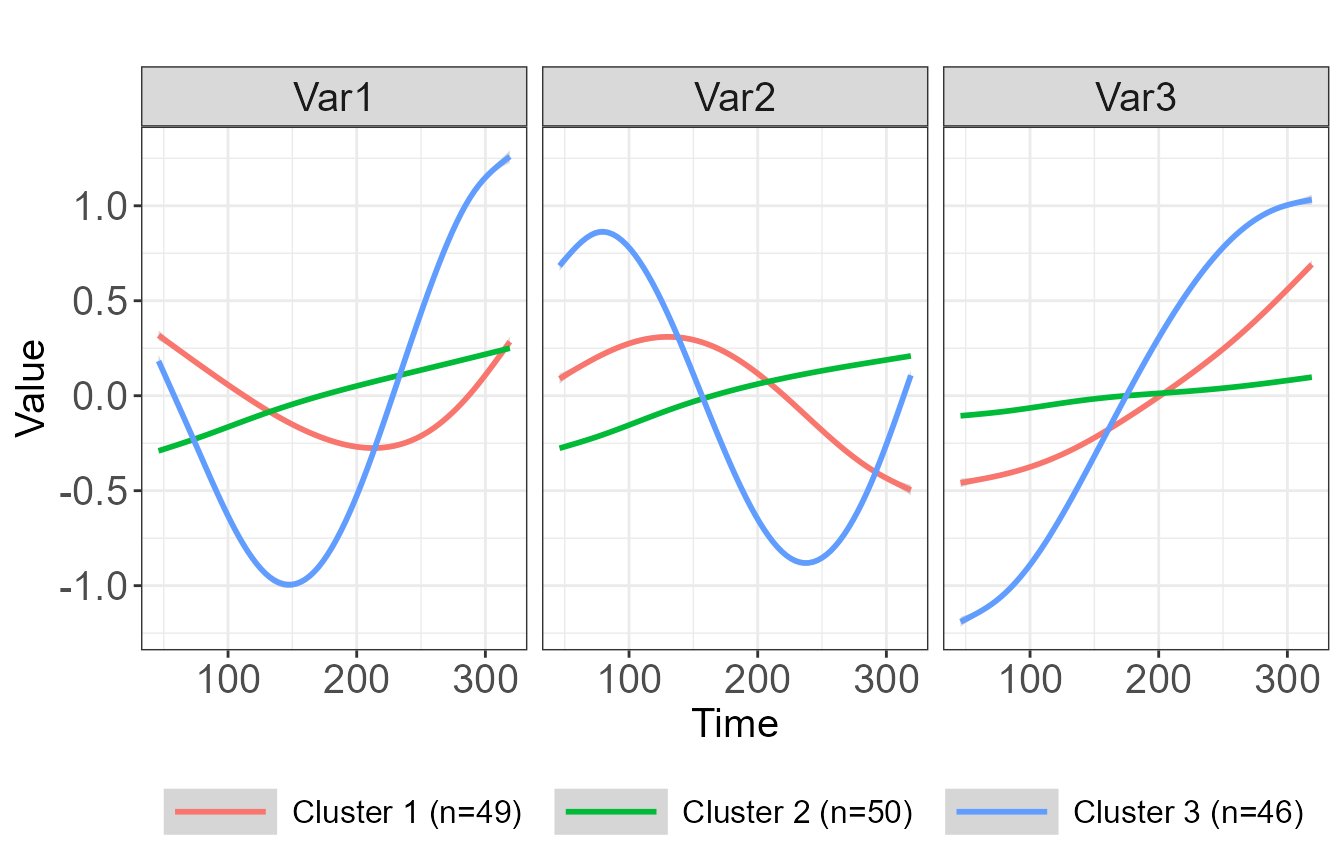

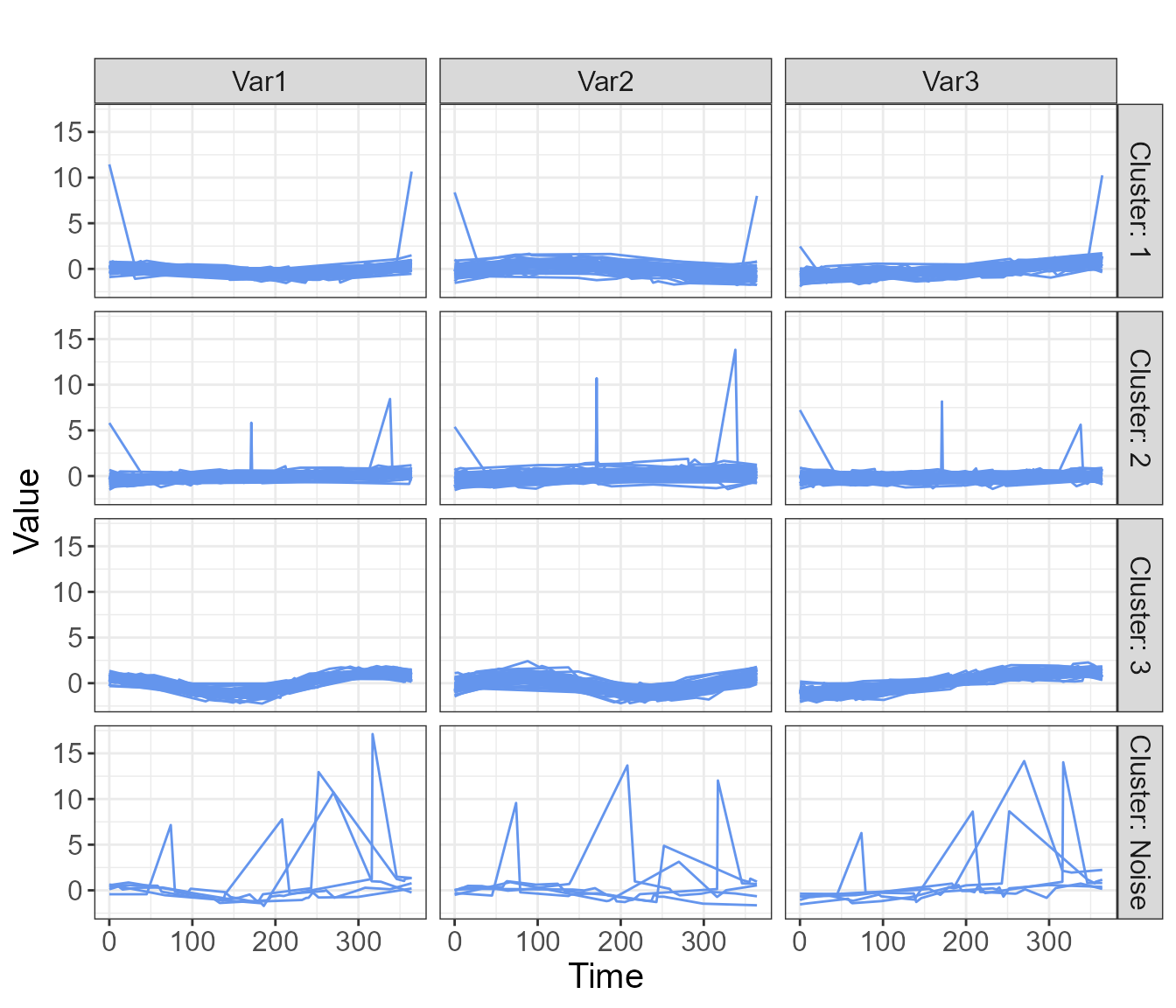

#> 6 6 83 2.273020e-04 4.444262e-05 9.997262e-01 2.035284e-06 3A number of graphics are available, including a plot showing the mean trajectory for each cluster, as well as spaghetti plots which may be overlaid or displayed in a grid format.

plot(cfit_3, type="mean", legend_label_size=12)

#> `geom_smooth()` using method = 'gam' and formula 'y ~ s(x, bs = "cs")'

plot(cfit_3, type="raw_grid", axis_label_size=12, strip_label_size=12)

The output dataset FKM_TPS_U contains the degree of

cluster assignment for each individual, as well as the modal cluster

assignment.

4.3 Fitting a GLM with fuzzy clusters as predictors in TPSClus

It is often of interest to examine the association between cluster

assignment and an outcome of interest. While using the modal cluster

assignment as an independent variable is fairly straightforward,

TPSClus provides a function for adding clusters into a GLM

using the partial assignment method described in section 3.2. The

function FKM.glm() uses the output object from

cluster.coefs() or cluster_fitted() along with

the original dataset containing an outcome variable of interest. It

retains the full functionality of the glm() function,

including the options for different family and link functions and offset

variables. Any number of fixed covariates may also be included as

independent variables in the model, in addition to the cluster

assignment. In the TS.sim dataset, we have two covariates,

x1 and x2, and a binary outcome variable. Therefore, we fit a logistic

model using the clusters identified previously, with cluster 1 as the

default reference cluster.

model <- FKM.glm(cfit_3, TS.sim, y="outcome", covariates=c("x1", "x2"), family="binomial")

summary(model)

#> Full model:

#> Formula (f1): outcome ~ Clus2 + Clus3 + Noise + x1 + x2

#> Family: binomial

#>

#> Call:

#> glm(formula = f1, family = family, data = data3)

#>

#> Deviance Residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -1.97354 -0.24706 -0.02364 0.15876 2.10229

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) 10.16346 2.04052 4.981 6.33e-07 ***

#> Clus2 0.98968 0.83743 1.182 0.2373

#> Clus3 2.22895 0.96709 2.305 0.0212 *

#> Noise 2.98192 2.15768 1.382 0.1670

#> x1 0.81151 0.67257 1.207 0.2276

#> x2 -0.26979 0.05146 -5.242 1.58e-07 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

#>

#> Null deviance: 201.065 on 149 degrees of freedom

#> Residual deviance: 65.561 on 144 degrees of freedom

#> AIC: 77.561

#>

#> Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 7

#>

#>

#> ANOVA chi-square p-value for significance of clusters in model:

#> 0.07274037We can see that assignment to cluster 3 is statistically significant in comparison to cluster 1 assignment. Overall, the p-value for the inclusion of clusters in the model is about 0.07.

4.4 Making predictions about new data in TPSClus

After clusters have been identified in a dataset or a model has been

developed utilizing those clusters as predictor variables, there is

often an interest in predicting the cluster assignment or outcome for a

new set of individuals. The predict functions in

TPSClus allow for both. In order to predict the cluster

assignment and degrees of cluster membership, we use the

predict function for the class 'FKM.TPS' of an

object output from cluster.coefs() or

cluster_fitted(), along with the new set of data. In this

case, we use the simulated dataset TS.sim.new, which

contains data for 30 new subjects.

cfit_pred <- predict(cfit_3, TS.sim.new)

summary(cfit_pred)

#> Object of type 'FKM.predicted'

#> predict.FKM.TPS(object = cfit_3, newdata = TS.sim.new)

#>

#> Tensor-product splines fit for 30 out of 30 subjects

#>

#> Degree of membership calculated based on clusters from input 'FKM.TPS' object.

#> 30 subjects clustered into 3 clusters + noise cluster

#>

#> Clusters based on fitted values at times 46 91 137 182 228 273 319

#> and slopes between points

#>

#> Cluster summary for new data:

#> Cl.size Min.degree Max.degree Mean.degree

#> Clus1 12 0.576 1 0.941

#> Clus2 10 0.909 1 0.991

#> Clus3 8 0.960 1 0.988

#>

#> Output dataset 'predicted_U' contains degree of cluster membership and modal

#> cluster assignment for each object.

#> Head of dataset 'predicted_U':

#> Id2 SubjectID Clus1 Clus2 Clus3 Noise ClusModal

#> 1 1 1626 5.894418e-09 0.9999999941 2.651672e-12 3.830269e-14 2

#> 2 2 1627 1.173724e-03 0.0003101768 9.985158e-01 3.041344e-07 3

#> 3 3 1629 2.177904e-02 0.0115980191 9.666197e-01 3.292821e-06 3

#> 4 4 1634 1.184537e-10 0.9999999999 2.314156e-14 2.220446e-16 2

#> 5 5 1641 7.284988e-01 0.2613819696 6.649319e-03 3.469900e-03 1

#> 6 6 1650 2.956685e-13 1.0000000000 6.299418e-17 0.000000e+00 2If we wish to predict an outcome for new patients based on the

previously developed model, we may use the prediction function with the

'FKM.glm' class object output from the

FKM.glm() function, along with the new dataset. It is not

necessary to predict the cluster assignments first.

pred_outcome <- predict(model, TS.sim.new)

head(pred_outcome)

#> SubjectID x1 x2 Id2 Clus1 Clus2 Clus3 Noise

#> 1 1626 0 23.5 1 5.894418e-09 0.9999999941 2.651672e-12 3.830269e-14

#> 2 1627 0 87.2 2 1.173724e-03 0.0003101768 9.985158e-01 3.041344e-07

#> 3 1629 0 59.3 3 2.177904e-02 0.0115980191 9.666197e-01 3.292821e-06

#> 4 1634 0 36.3 4 1.184537e-10 0.9999999999 2.314156e-14 2.220446e-16

#> 5 1641 1 49.6 5 7.284988e-01 0.2613819696 6.649319e-03 3.469900e-03

#> 6 1650 0 34.1 6 2.956685e-13 1.0000000000 6.299418e-17 0.000000e+00

#> ClusModal predicted

#> 1 2 9.919424e-01

#> 2 3 1.457288e-05

#> 3 3 2.486555e-02

#> 4 2 7.957166e-01

#> 5 1 1.069007e-01

#> 6 2 8.758032e-01

summary(pred_outcome$predicted)

#> Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

#> 0.000000 0.001644 0.274358 0.409432 0.833822 0.999997The predicted value in the output dataset is the predicted

probability of the binary outcome. Adding a type = "link"

option would give a prediction on the scale of teh linear predictors.The

mean value of the predicted probability is about 0.41.

5. Summary and discussion

The TPSClus package provides a methodology for

multivariate fuzzy clustering of longitudinal data and for inclusion of

fuzzy clustering results in a GLM to predict a distal outcome. The

package provides multiple plots to enable visualization of the clustered

data. Cluster assignment may be used as a predictor in a GLM while

taking the uncertainty of cluster assignment into account. In additional

the package provides options for predicting cluster assignment and

outcomes for new data.

Limitations of TPSClus are those inherent in all

clustering algorithms. The methods identify clusters based entirely on

trajectory shapes, but in reality, these clusters are a construct for

simplicity of interpretation and are not well-defined in a real EHR

dataset. The determination of the optimal number of clusters remains an

unsettled issue. In this package, we provide several indices and plots

to help make the decision on the number of clusters to use, but the

indices often disagree on the optimal number of clusters, and there is

no index that is widely accepted as being the most reliable.

There are few packages in R that allow for clustering trajectories on

multiple variables simultaneously. The TPSClus methodology

is non-parametric, avoiding issues with assumptions about trajectory

shape and computational cost associated with GMM models. In addition,

the package offers options for robustness to outliers and for including

the clusters into GLMs as independent variables. It also provides

valuable visualization tools.

Topics needing further investigation include identifying the optimal number of clusters and a comparison of the various methods that have been presented in the literature for clustering multivariate trajectory data.